In November 2024, French President Emmanuel Macron refused to travel to Baku in Azerbaijan to attend COP29. This absence bears the weight of the historic alliance between France and Armenia, a nation in conflict with Azerbaijan for decades, with tensions escalating in 2023, causing the displacement of more than 120,000 Armenians, or close to the entirety of the Nagorno-Karabakh’s population, as well as hundreds of deaths. The conflict mainly takes place in Nagorno-Karabakh, or Artsakh for Armenians, in the southeast of Armenia. The war waged by Azerbaijan is deadly, violent, as some compare it to the Armenian genocide carried out by the Ottomans in 1915-17.

Although international relations are part of our curriculum at Sciences Po, this conflict is rarely discussed. By deciding to write an article on this subject, and with the help of Gevorg and Ani, we hope to raise awareness about the Armenian cause when the French president’s decision was not enough to bring the war back to the forefront of the media. Ani is a second-year student and Gevorg is a first-year student, both in the EURAM program in Reims. Gevorg has lived most of his life in the capital of Armenia, Yerevan, whereas Ani moved to France ten years ago. They are both very attached to their homeland, and as Ani says, “[her] heart is still in Armenia.”

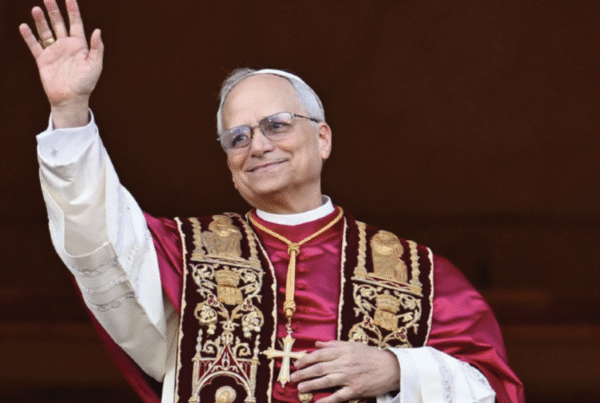

The Sundial Press also spoke with Vincent Duclert, a French specialist on the history of genocide. He often speaks publicly to denounce the current situation in Nagorno-Karabakh as an act of genocide.

A History of Tensions

Gevorg and Ani are proud Armenians, but behind the pride there is also the question of survival as a nation, as the country is a recurring target of Azerbaijani and Turkish nationalism. Indeed, in 1915, Armenians were victims of an extermination campaign by the Young Turk government of the Ottoman Empire. Their goal, initially hidden but later revealed by archives, was the ethnic and religious homogenization of the region. Thus, 1,5 million Armenians ethnically cleansed while most survivors fled into exile. The genocide, still not recognized by Turkey today, holds a large place in the collective memory of the country. In fact, the legacy of this mass extermination still remains in the landscape, while its eastern neighbor, Azerbaijan, has inherited Turkish and Muslim nationalism in the region in opposition to Christians and Armenians. “They want to create a unified Muslim world without Armenia. […] Azerbaijan and Turkey share strong ties, and their goal seems to be reconnecting culturally and geopolitically,” Ani said. Both Turkey and Azerbaijan officially describe themselves as “one nation, two states,” recalls Gevorg. Duclert adds that these two countries, Azerbaijan and Turkey, are also linked by their denial of the first genocide, which they still justify as a response to the threat that Armenia allegedly represents for them. He observes a constant in history since Azerbaijan is said to have resumed the genocidal project, a key example of which is the Sumgait pogrom in 1988 during the first Nagorno-Karabakh war.

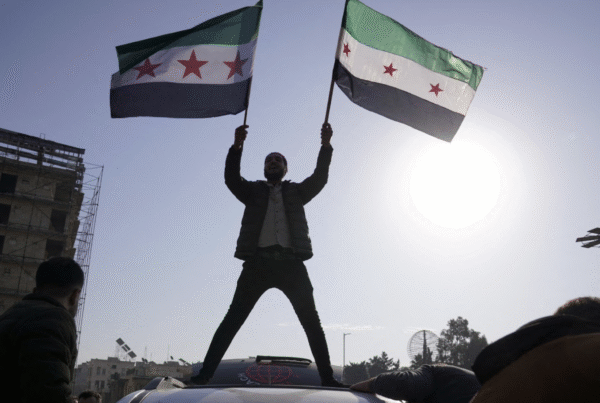

The 1991 proclamation of independence of Nagorno-Karabakh, following the fall of the USSR, a territory populated almost exclusively by Armenians, triggered conflicts between Armenia and Azerbaijan over their influence and military presence in the region. The first war, fought from 1988 to 1994, ended with Armenia gaining control of the region. However, tensions persisted, and in 2020, Azerbaijan, backed by its ally Turkey, launched a successful military offensive, reclaiming significant portions of Nagorno-Karabakh. Despite a ceasefire agreement, the conflict remained unresolved until 2023, when Azerbaijan fully annexed the region, ending decades of dispute and solidifying its sovereignty over the territory.

“We are once again in Baku with our brothers to renew our strong support for dear Azerbaijan and exchange (views) on the latest developments in Nagorno-Karabakh,” Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlut Cavusoglu said on Twitter in 2020, following the beginning of the war. It is in this same context, as well as the rise of tensions in 2022 and 2023, that Azerbaijan has been accused by the Armenian government of pursuing actions described as genocidal. These allegations include reports of mass executions, chemical weapons attacks, and bombings in Nagorno-Karabakh, aimed at strengthening control over the territory and advancing its ethnic and religious ideology. “The reasons for this extermination are historical, religious, geopolitical, and geostrategic,” adds Gevorg. “They know the amount of power that we hold as a nation. […] It is always a question of major powers establishing themselves over the minor powers.”

An Impossible Peace?

Peace existed in the region between 1994 and 2020, between two wars, and it is in this context that Ani and Gevorg grew up. However, as the latter points out, Azerbaijan violated its own peace treaty, which explains the defeatism with which Armenians approach the issue of possible peace. “Having peace is in our interest, but on the other hand, it is impossible to have peace when what the other side ultimately seeks is the complete eradication of Armenia. That is why thinking about peace seems impossible to us,” Ani states pessimistically. “For them, peace will only be possible with the eradication of Armenia. Their peace is not our peace. Mutual peace is unattainable,” Gevorg adds.

Like Gevorg and Ani, the Armenian diaspora is vast and spread across the world and is an asset, as Ani said: “the diaspora is a strong part of what makes us Armenians, because even after the genocide, we are everywhere, rebuilding ourselves and fighting for the country. Having people all around the world helps, because they are raising their voices and standing up for Armenia, like Charles Aznavour. Thanks to him and others like him, more countries know what is happening there. Some might see the diaspora as a weakness, but it’s really more of a strength”. Indeed, the diaspora represents around 7 million people, including approximately 500,000 in the United States, such as the Kardashian family, and more than 600,000 in France. “The existence of the diaspora itself is evident proof of the Armenian genocide that Turkey is trying to deny,” Gevorg said.

The Armenian diaspora, in addition to providing financial and development support to the country, partly helps to gather allies, which has led to the recognition of the 1915 genocide by parts of the international community, as well as to raising awareness. This is how Ani shares her childhood dream of wanting to “restore Ani” (one of the former capitals of Armenia, currently in ruins within the territory of Turkey, and from which she got her name). Today, she believes that her role, especially as a Sciences Po student, is to become a public figure, to acquire diplomatic skills and to return to Armenia to participate in resolving the situation.

A silent international community

Despite the deadly conflicts and the beginnings of what has been described as an ethnic cleansing enterprise, the international community appears largely unresponsive. “Countries have neither economic nor political interest in Armenia, especially compared to Ukraine,” Ani suggests. This can also be explained by a complex web of alliances, as Azerbaijan is allied with Turkey and Russia—two significant powers that many countries are reluctant to offend. Russia, for obvious reasons of geopolitical influence, and the fact that the conflict in Ukraine already demands substantial military and diplomatic attention from the West. Turkey, on the other hand, wields considerable leverage through its control of migrant flows into Europe. “When Emmanuel Macron publicly expressed his support for Armenia, Erdogan made it clear that he did not approve,” Ani points out. “It’s just not worth it for them,” summarizes Gevorg. Vincent Duclert, however, believes that scientific knowledge must be communicated to the public to inform their decisions and bring ignored issues to the forefront. Thus, he has written numerous articles in the press in the hope of publicizing the dramatic situation in Nagorno-Karabakh. These statements contributed to a political awareness in France, notably with official recognition of “ethnic cleansing” by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Ultimately, the resilience of the Armenian people remains their greatest weapon in this conflict, as the small nation stands alone and weakened. Armenians are calling for an international response, including grassroots efforts, as Gevorg and Ani emphasize: “It’s important to stay informed and take

the time to understand historical events, there’s so much they can teach us.”

Other posts that may interest you:

- COMPRENDRE L’IRAN: Des jeux d’alliances, et une société en pleine mutation (2)

- COMPRENDRE L’IRAN : Quand l’Iran s’impose sur la scène internationale

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.