by Ning Chang

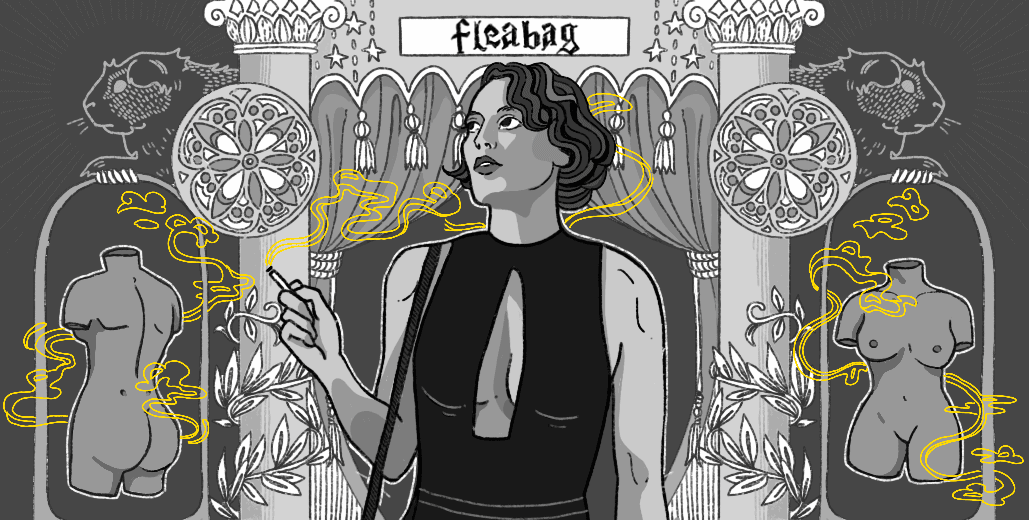

What is it about Fleabag that makes women want to see themselves in her? The dryly sarcastic, deeply traumatized, and absurd character of the eponymous TV show played to perfection by Phoebe Waller-Bridge is seemingly inescapable for millennial women inEuro-American societies. Her fucking up, fucking around, and simply fucking, are characteristic of her messy interior life, which she invites the viewer into through a fourth-wall-breaking glance or coy comment. Fleabag is a deeply vulnerable, deeply flawed character whose laundry list of tragedies, dissatisfactions, and unhealthy coping mechanisms should not be envied by anybody. So what can explain Fleabag’s commercial and critical success, or why women on Tik Tok and Twitter post wryly about being in their “Fleabag era”?

I would argue that the appeal of Fleabag comes from a more recent reconsideration of womanhood centered on an internal approach to suffering and self-destruction, characterizing it as inherent to the female condition. In season 2, Fleabag has a conversation about female pain with Belinda, a businesswoman portrayed by Kristen Scott Thomas. The women discuss menopause, pregnancy, and periods, and Belinda comments, “Women are born with pain built in. It is our physical destiny.” Why has this statement resonated with so many women? What does it say about the natural condition of a woman (or really, people with uteruses) that we now expect the chief commonality among us to be suffering?

This edgy new understanding of femininity was discussed by Emmeline Clein in a think-piece for Buzzfeed titled “All the Smartest Women I Know are Dissociating,” where she coins the term dissociation or dissociative feminism to describe the current post-feminist moment. She elaborates: “We now seem to be interiorizing our existential aches and angst, smirking knowingly at them, and numbing ourselves to maintain our nonchalance.” We see this in other prominent female figures in the cultural discourse— Sally Rooney’s heroines in her novels Normal People and Conversations with Friends feel restless and detached in their own skin; Ottessa Moshfegh’s My Year of Rest and Relaxation is a listless and drug-fueled inventory of ennui “experienced” by its dissociating protagonist; Rue Bennet from Euphoria seeks self-understanding while aiming to keep reality and its demands at a distance. All these characters speak to the popularity of an oblique and ironic self-awareness that valorizes pain to a point where it becomes self-destructive.

I would contend that defining the female experience as one dictated by pain encourages a sort of self-pity that plays an integral part in keeping women passive. We normalize pain and suffering in a way that discourages us from seeking solutions to fix it. Arguably, not fitting the mold of being a tidy and docile woman is a fair way to rage against the machine of the patriarchy and presents a new dimension for female characters on screen. But simply accepting it as a condition of real womanhood is to accept it uncritically, or worse, self-critically. Thinking of it as a collective problem and then choosing to individualize and privatize it ends up stifling our capacity to be active about it. With the focus turned inwards, we minimize the problems we face as women and forget that they are deeply and insidiously rooted in a patriarchal society. We hold our pain so closely, intellectualize it, and dissect it to poke fun at it, that we end up losing ourselves in it and shying away from any promise of a life without it. In this jaded perspective of our interior lives, we hardly ever blame society, only ourselves. We lose the impetus to address the social and systemic issues at the heart of this struggle. At the end of the day, it keeps us submissive.

The other important factor of this story to consider is that of privilege and the dangers of taking a universalist approach to what is essentially a new form of upper class, millennial, white feminism. Fleabag was showered with awards for being “relatable” in its tragicomedy. Girls, with Lena Dunham, was a story for real millennial women, their trials and tribulations in excruciatingly painful honesty. But who is this meant to be marketed to, who does this truth belong to? The audience of young, white, affluent women who grab onto these relatable characters and seek to mold themselves into their suffering end up causing more damage. In this pursuit of recognizing their imperfection, this class of women often neglect the privileges that they have.

This specific type of self-dissection is only accessible for a certain group of women. Other women, especially those who lack the same cultural and economic capital, do not have the time, money, or security to be this self-reflective, to be petulant and unlikeable, to consider the ennui of having it all and also having nothing. Could you imagine a black woman’s anger being treated as a Fleabag-era moment? Or a working-class mother having the space and time to relate to and indulge in the wallowing that has been valorised in My Year of Rest and Relaxation? These women are also the ones who suffer the most from this intentional ignoring of social agency caused by the turn inwards, who suffer from this slowdown of feminist progress.

Blogger Rebecca Liu writes about this in a post, remarking on “the curious case of how these particular women, ostensibly furnished with all the social trappings to take over the world – white, wealthy, pretty, ever-amenable to men in spite of their worst efforts – prefer to turn their gaze inward to hate themselves (…) Why are the very women who, in theory, hold the most social power so interested in divesting themselves of it?”

Despite my criticisms of dissociative feminism, I would clarify that dissociative feminism has not wrecked the idea of “feminist progress” in a drastic way. Sure, the internalization of the struggle is not very helpful for dismantling the oppressive structures of patriarchal society, but it is not something that we need to lose our minds over. Rather than seeing dissociative feminism as a new era of feminism, it might be more optimistic to see it as a reactionary period in line with the Hegelian view of progress as dialectical – an overcompensation for other extreme interpretations of feminism

In the canon of potential successors to third-wave feminism, dissociative feminism comes as a reaction to girlboss feminism. According to Liu, the creators at the forefront of this dissociative feminism trend were “relentlessly bombarded with the message that women can do anything and be anything, and especially women like them.” This “you can do it!” view on life has translated directly into this era of lethargic rebellion— you might fail at doing it all and feel like squandered potential, or you can do it all and still be unhappy. Dissociation feminism points out the limits to leaning in, to doing it all, to carving new paths and shattering the glass ceiling, and the personal toll these expectations can take. But the mistake is to see dissociation feminism as an emancipatory alternative. Just like girlboss feminism, it normalizes the status-quo of women today— whereas one attempts to superficially rehabilitate neoliberalism, the other is still deeply disempowering and normalises an unproductive form of self-hatred and isolation. This is obviously not to say that women can choose not to be depressed or lost, or that it is easy to climb out of this overly self-conscious mentality— the grievances of the upper class, young white women are not insignificant in nature. But we have to stop valorizing and normalizing this navel-gazing and individualist approach to “feminism” that deadens an effective approach to solving the issues that cause us this pain and suffering. We need a new, restorative turn that refocuses our attention on the collective, the political, and the structural efforts of feminism.

So, keep enjoying Fleabag. Continue to self-reflect, to read My Year of Rest and Relaxation, and to seek an awareness of your own trauma. But do not simply stop there, do not spiral, do not retreat into the anonymity and state of suffering that has been prescribed for us by a culture that seeks to neutralize the collective issues we face as a feminist movement. Let womanhood in all its messiness, tragedy, and brilliance be reconsidered and recognized, but do not forget that it is within our capacity to strive for better.

Other posts that may interest you:

Discover more from The Sundial Press

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.